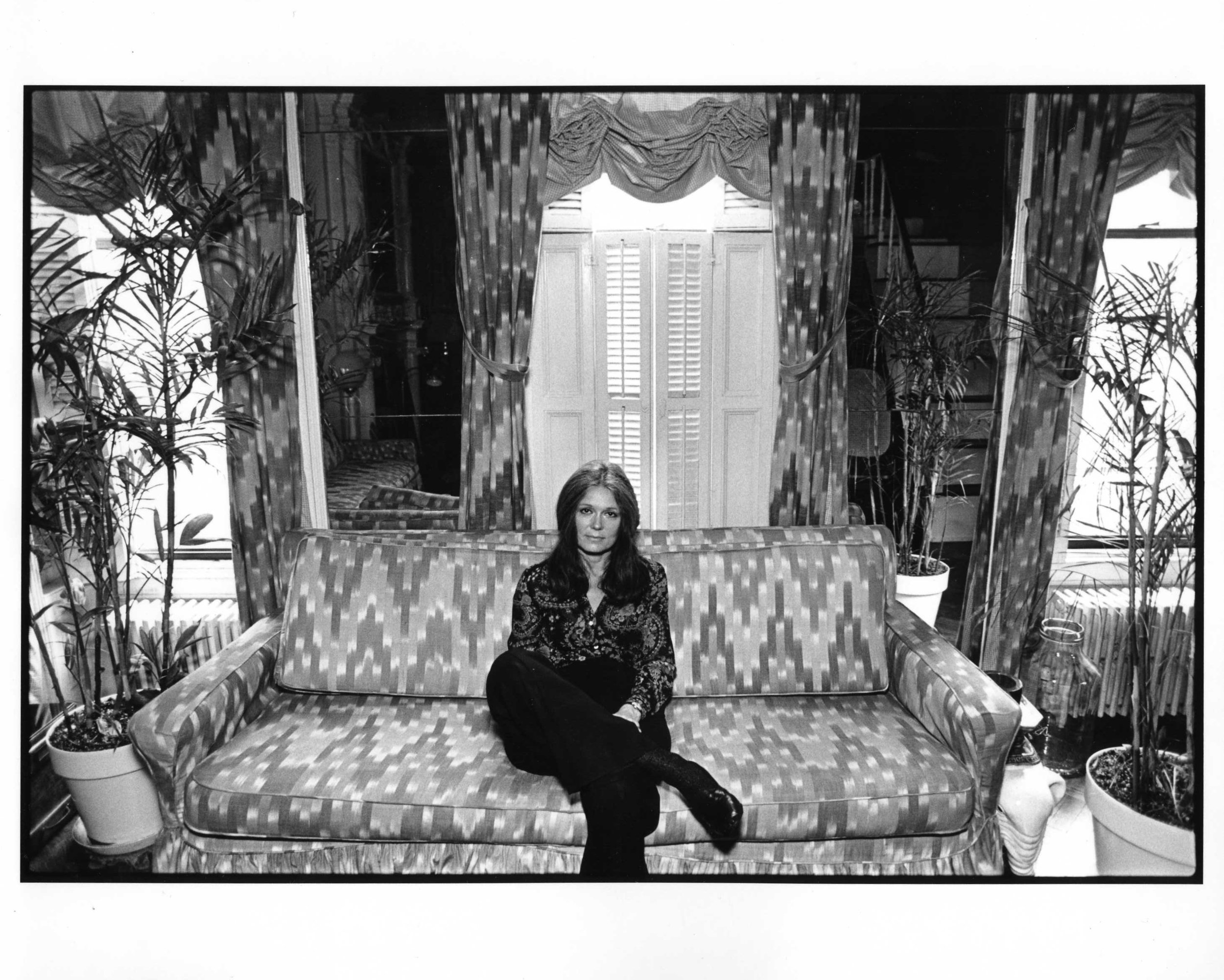

Gloria's Foundation

Honoring the lifelong work of feminist icon Gloria Steinem, Gloria’s Foundation is dedicated to advancing the feminist movement. Our immediate goal is to preserve and maintain Gloria’s iconic three-story Manhattan apartment—a historic hub of activism, creativity, and community.

As Gloria herself said:

“My apartment isn’t just a home; it’s a political center. It’s where people have come to feel safe, and I hope it can continue as a sanctuary for the feminist movement.”

Since 1968, this beloved brownstone has housed feminist leaders, thinkers, and organizers. From the birth of Ms. Magazine to grassroots meetings that shaped the feminist movement, this space is more than a home—it’s a cornerstone of feminist history. Our mission is to preserve this legacy for future generations, safeguarding both the space and its role in advancing feminist causes.

A Hub for Feminist Activism

Gloria’s apartment has served as a gathering place for organizers, activists, and scholars from around the world. From fundraising events to quiet retreats for international feminists, the brownstone has been a place where radical ideas and organizing efforts flourished. Organizations like the Third Wave Foundation, Equality Now, and the Women’s Media Center began here, drawing strength from the sense of community Gloria’s home fostered.

We’re working to preserve this space and its archives—handwritten letters, conference notes, and other artifacts—so that future generations can learn from the trailblazing feminists who shaped our world.

Your Donation Matters

Your contribution to Gloria’s Foundation helps preserve this vital feminist landmark and fuels the ongoing work to foster activism and community care. Your support will ensure that Gloria’s apartment continues to inspire and empower future leaders in the feminist movement.

Gloria’s Foundation Inc. is a 501(c)(3) private operating foundation.

All donations are tax-deductible as allowed by law.

Gloria’s Foundation accepts stock transfers. If you are gifting via a Donor Advised Fund, please reach out to hello@gloriasfoundation.org.

Contact